by Rodman B. Miller, M.D.

Plantation medical care played an important and integral part in the development of health care in Hawaii. At one time plantation laborers numbered as high as 53,000. Including dependents there were about l03,000 individuals cared for by plantation physicians just after the tum of the (20th) century.

At first, provision of care was probably philan- thropic to a degree, but certainly its purpose was to maintain healthy, productive workers. Significant concerns were malnutrition (with beriberi the pre- dominate vitamin B1 deficiency), tuberculosis, vene- real disease, respiratory infections, maternal and child care (again, nutrition was most important), infant diarrhea, and immunization. Vaccines were given as they became available, including diphtheria and smallpox. Along with the above came better surgical and orthopedic care, hospitalization where needed, and diagnostics to discover disease. This included x- rays for tuberculosis and testing of infants for anemia which was done on a wide basis during the 1930s.

The economic development of the Islands cer- tainly proceeded in parallel with the growth of sugar and pineapple production, and medical care went hand in hand. The 103,000 people constituted a little less than a third of the entire island population of about 368,000. The availability of medical care gradu- ated from sporadic coverage to full coverage by the individual plantations, and then to an industry-wide medical care system. Originally care was provided free, but sometime after the labor unions came, costs were levied on the members. The charges were extremely low and did not represent the full expense to the plantations.

We don’t have much information before the I880s. Early pioneers included missionary doctors such as Dr Gerrit P. Judd in the 1850 era. Judd cared for all comers, with repayment being the possible conversion of patients to Christianity.

In 1888 Dr Luis F. Alvarez served as the doctor in Waialua, Oahu covering plantation and non- plantation patients alike. His son, Walter, witnessed kitchen-table appendectomies and amputations. Dr Walter Alvarez subsequently became a consultant of national renown in the field of internal medicine. The site of his home was behind the present Waialua district gymnasium in Haleiwa.

Dr Charles Davis described medical care in an article in 1904. It appears that the art of medicine prevailed over the science. Dr Davis, who was then the Ewa Plantation physician, displayed much hu- manity for foreign laborers. He says, “I treated over 180 patients every day of the year.” His philosophy included removal of the causae morbi (cause of the disease). “I would let no man go from my office who thinks he is sick, empty-handed.” Also, “Pass not idly by the patient who thinks he is sick, for indeed he is.” For diarrhea he gave cathartics such as calomel and then sedation with tincture of opium.

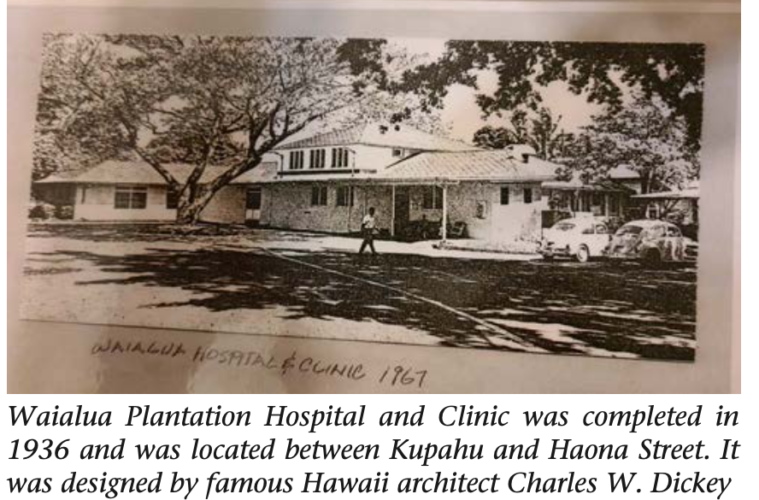

Subsequent plantation physicians included Dr Fred Irwin and Dr L.D. Sexton, who, in the tradi- tion of general practitioners at the time, traveled by buggy through muddy roads to do deliveries, appendectomies, etc., with instruments sterilized in the kitchen. Typhoid fever was a particular problem during 1906 to 1907. Hospitals were few at the turn of the century, but by the 1930s each plantation had its own or shared one with an adjacent plantation.

In 1930, the Hawaii Sugar Planters Association (HSPA) appointed Nils P. Larson MD as medical advi- sor, and with his help, strove to improve plantation workers’ health through a study of diet and the use of supplements to the polished white-rice diet the workers and their families preferred. Other facets of health needs were also studied. The plantation bul- letin, Plantation Health, disseminated information to physicians discussing and helping to solve common problems. Dr Charles Wilbar was the editor and Dr Larson was the plantation consultant for Plantation Health. An organization for plantation physicians was formed, and periodic meetings were held with speakers on pertinent topics.

Note: Dr. Miller joined the Waialua Agriculture Company as a plantation physician in 1961 for five years before opening his private practice in Hale‘iwa in the old Kua ‘Āina building. It is now the Queen’s Hale‘iwa behind First Hawaiian Bank. Article reprinted with permission from the Hawai‘i Medical Journal, Vol 54, November 1995.